Building Habits for Long Term Results

Recently, I managed to establish two habits that I have incorporated into my daily life: resistance exercise and writing, two activities that I didn’t even like for a while. However, once I was able to solidify them as habits, I not only do them regularly but also enjoy them, and I even look forward to the time spent doing them.

As a result, I have set aside other less healthy activities, which has contributed to increasing my overall satisfaction and well-being, or what we also call happiness.

I have successfully maintained these two habits despite facing some challenging situations that would normally affect their consistency, such as a couple of colds, work-related stress, long workdays, family outings, and various other factors.

For the first habit: engaging in strength and resistance exercises, I have been doing it regularly at least 6 times a week (mostly at the gym) for a year now.

The second is the wonderful habit of writing, which I have been consistently practicing for the past 10 months. Since then, I have been able to write approximately 300-400 words daily on average, continuously and regularly, despite encountering some difficulties along the way, such as my laptop keyboard breaking or periods of low inspiration for new topics. In Particular, many days I simply didn’t feel motivated enough to do it.

Choose your pains, designed quote created with ByPeople Composer

Why is it Challenging for Us to Establish Habits?

A few months ago, my brother managed to lose 35 kg of weight through a balanced combination of diet and cardiovascular exercise. This has positively and radically transformed his life in every possible way: he now feels more energetic to face each day, has incorporated new activities into his life like cycling, and through this, he has been able to meet new people. His self-confidence has improved as he feels better about his body, and his overall relationship with others has become healthier.

However, there is one activity he hasn’t been able to undertake: strength and resistance exercises. I recently asked him why he hadn’t succeeded, and his response aligns with one of the main reasons that evidence has shown hinders the proper formation of habits in many individuals: lack of sufficient motivation to do so.

We could call this problem the vicious circle of habits: We wait to have motivation to do an activity we don’t like or that causes some friction. As a result, we only perform it when we are genuinely motivated to do so. However, this inconsistency prevents the activity from becoming a constant habit that can truly solidify. Consequently, it doesn’t yield the desired results, and thus, the motivation required for it to become an enjoyable activity, free from interruptions, never develops.

This problem is quite common when we try to incorporate a habit related to an activity we don’t particularly enjoy or are unfamiliar with. For example, if we are not used to exercising and want to start, that activity will create a lot of resistance for our bodies and, more importantly, for our minds, because it’s something we don’t necessarily want to do. In fact, we might not even know how it feels to do it.

If we want to start eating healthily but have never done so, it will be challenging to muster the necessary motivation every day to establish it as a habit, considering that a habit can take anywhere from 21 to 250 days to solidify. We should also understand that an activity truly becomes a habit not only when it’s done regularly but also when it’s done thoughtfully, regardless of the circumstances. In other words, we should be able to perform the habit without external factors or third parties influencing our decision or motivation to carry it out.

The Key: Don’t Wait to Feel Motivated

The solution to this problem is to start with an action that, although it may seem quite simple, can become genuinely challenging over time. It simply involves not waiting until we feel motivated to perform the task we want to turn into a habit.

When a habit is not ingrained in our brain, we should not wait until we feel motivated enough to carry out that action. Instead, we should do it even when we don’t want to or when we lack enough enthusiasm. However, it’s worth noting that performing exercise without enjoying it doesn’t release the same amount of dopamine (the hormone responsible for our motivation) in our bodies as doing it with enjoyment. Therefore, we can use some tools to overcome this initial friction.

Don’t wait to be perfect, you can start now! Created with ByPeople Composer

Staying Motivated Throughout the Process

Creating a plan will always yield better results than going at it blindly. So be specific! If your goal is to learn German, creating a schedule to “study German for 20 minutes, three times every week” is a much better way of phrasing it, rather than a vague thought of “learning more German this year”.

Also, having some kind of accountability, such as using a tracker app or a friend, will help you stay consistent and monitor your progress, which in turn will push you to keep going. It also goes without saying that it is much easier to stay consistent on something you want to do out of interest than it is to stay consistent on something you’re doing out of a belief that you should do it.

Positive reinforcement, coming up with some reward system, will also aid you in your journey. Researchers have found that rewards received during the activity work much better than rewards received after the fact.

Setting Long-Term Goals

The first tool is learning to set long-term goals and visualize their outcomes. This way, we can associate our habit with a goal and think of that goal as a method of motivation. We imagine ourselves being able to play that guitar song we love or seeing ourselves in the mirror with the athletic body we’ve always dreamed of.

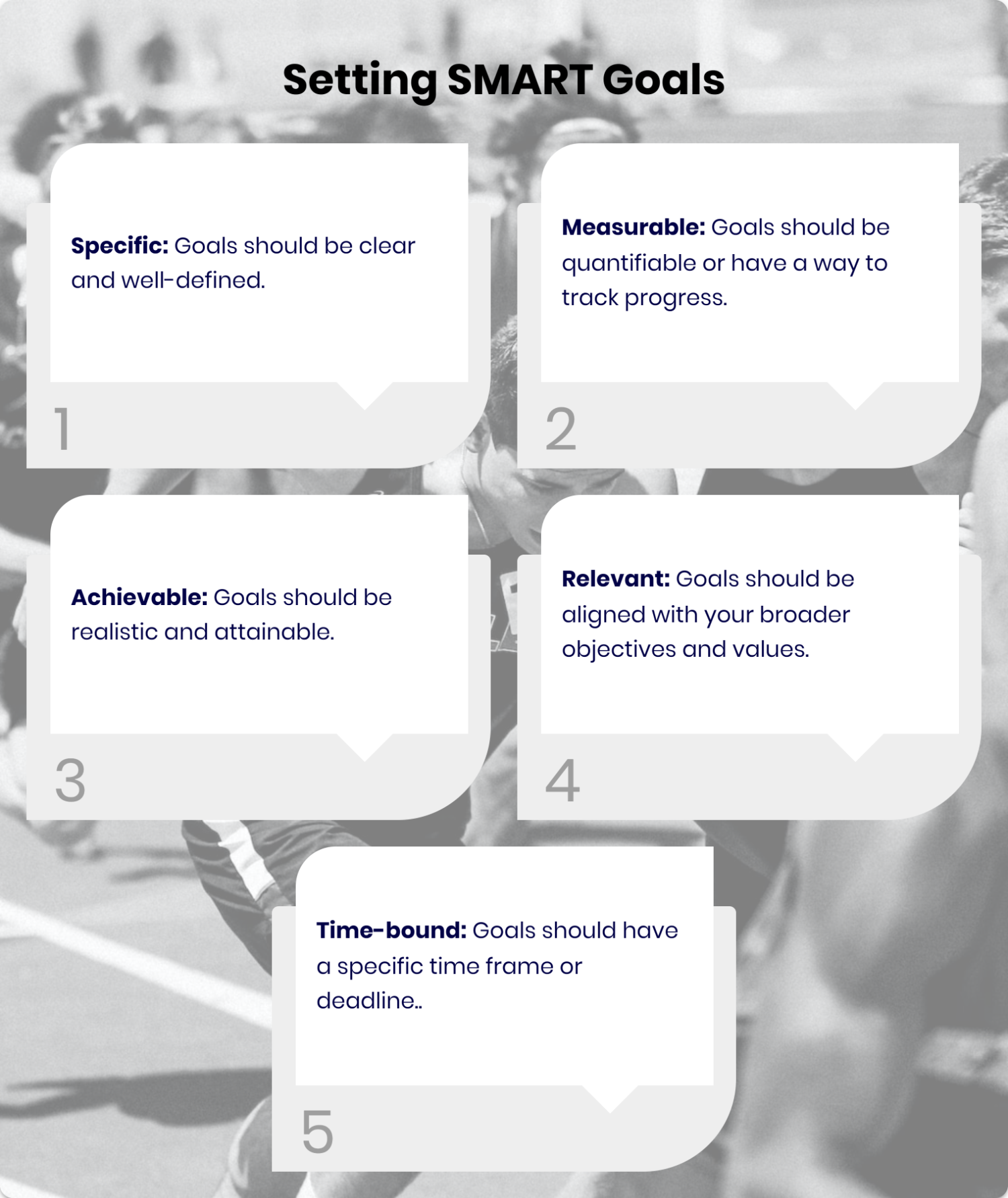

Setting long-term goals associated with the habit we are developing can be done using the SMART technique to ensure that the habits have the following characteristics:

- Specific: Clearly defined, not vague.

- Measurable: Results can be measured over time.

- Achievable: Goals that are realistically attainable.

- Relevant: Objectives that are aligned with your purpose.

- Time-bound: They have a deadline to achieve the results.

SMART Goals technique. Image created with ByPeople Composer

Visualizing these long-term goals generates initial motivation to start the task and allows us to associate that daily or regular activity with a specific objective, rather than doing it without a future purpose. This is why gyms are busier between January and March.

The problem is that this initial motivation can fade over time, and we may start neglecting the task until we abandon it altogether.

As a self-taught musician, I’ve learned to play five different instruments on my own, in addition to music theory and singing. I’ve heard the following phrase countless times: “I started playing the guitar, but after a few months, I abandoned it and never continued. Today, it’s stored in a closet.”

The problem lies in the fact that as the days go by, situations will arise that make it challenging to carry out the task we want to establish as a habit. For example, if we’ve been exercising somewhat regularly but suddenly encounter a rainy season, have a week where we’re not very motivated, or experience an unusually heavy workload that leaves us feeling tired, we may abandon the activity because we lack the motivation to do it given the circumstances.

This is precisely the problem we need to address. It’s during these moments of difficulty that we must prepare our minds the most to carry out the habit, even if we have to force ourselves to do it without having sufficient motivation. What we need to discover is the satisfaction of fulfilling that habit and the positive results that stem from it. This satisfaction will be even greater if we initially didn’t have the desire. The fact that our brain senses that we were able to complete the task will generate an extra dopamine boost and reward us with motivation, precisely because we managed to accomplish it despite the challenges.

It’s important to note that we can’t simply deceive the brain. We can’t make it believe that we enjoy the task if we don’t. However, if we learn to enjoy the feeling of having completed that activity, it will be easier for us to overcome the friction it generates.

This is why making the bed as the first action of the day is a fundamental task to activate our brain. We are telling it that we were able to start the day by completing a task satisfactorily, and this is very healthy for our brain. It motivates us, even if making the bed isn’t particularly fun or enjoyable. What is enjoyable is the result: knowing that when we return from work, our room will be tidy.

Recognizing the Inherent Benefits

If we have managed to set long-term goals and directly relate them to our habits, the results of those goals will motivate us as we achieve them. However, there are advantages or rewards inherent to habits that, if we can anticipate and acknowledge, will help us in habit formation, especially during moments when we have low motivation.

I would like to offer some examples to better explain this point:

If you exercise regularly, it is quite likely that on the days you exercise, you will be able to sleep better, something that the evidence has widely shown. A good night’s sleep is tremendously beneficial for your body and mind, so if you can associate the habit with this “reward” you are receiving, you will feel extra motivation to carry it out, and these rewards are almost immediate; you don’t have to wait long to start seeing the results.

If you engage in strength and endurance exercises, you will likely feel the need to eat more, which is a real pleasure for many. This extra appetite is an immediate reward you gain from the execution of the habit.

If you keep a journal in which you record your concerns and possible solutions to those problems every day, you will also be addressing your rumination, which is known to not only generate anxiety but also affect your sleep. It is a reward you are receiving that is inherent to the habit.

If you establish the habit of three good things, which involves thinking or writing down three good things that happened to you during the current day or the previous day, even on difficult days, your level of optimism will improve, which also helps in dealing with issues like depression and anxiety. Science has shown that this simple exercise can help you combat these situations in a short amount of time.

Any healthy habit you acquire will make you invest your time more productively. Almost without realizing it, you will be replacing time that you used to waste on unhealthy habits with better-utilized time. This way, you will feel more productive and feel that you are achieving your goals day by day. We have covered this topic before on this social media detox guide!

As you can see, if we can recognize these rewards that are inherent to healthy habits and think of these rewards as part of the advantages we are receiving for carrying out the habit, we will have extra motivation to continue with that activity.

Knowing the Habit in Advance

Design created with ByPeople Composer

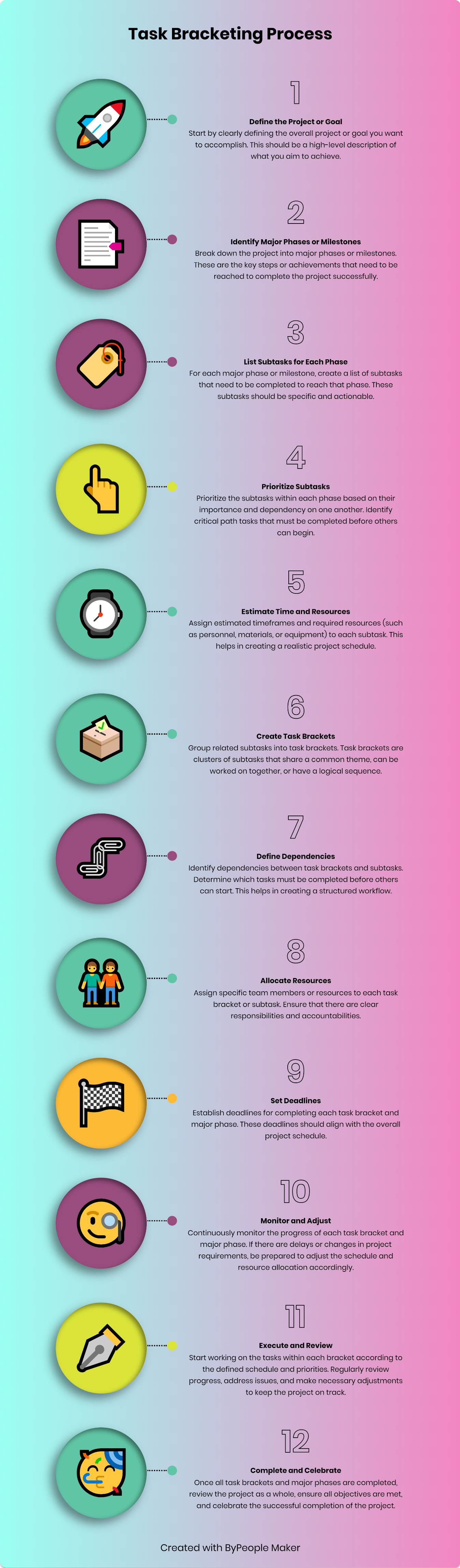

The second strategy is to have a deeper understanding of the task we are going to perform and be able to use the Task Bracketing technique. Perhaps you’ve noticed that musicians can learn to play a new instrument with extreme ease or that polyglots can learn a new language much faster than an average person. The reason is that they already know the activity through their past experience. They’ve been through it, they know its processes, how to identify difficulties, but above all, they know they must be patient because the activity will yield the desired results.

Knowing the activity more thoroughly makes it easier to carry it out and maintain it over time. If you’ve never been to a gym and go for the first time, you can feel lost and disconnected. Moreover, you won’t be able to plan the activity you’re going to do on the current day in advance. This process relates to a technique called Task Bracketing, which involves visualizing and thinking about these activities in advance as a complete step-by-step process, from before starting the activity to after completing it, along with the satisfaction that completing it brings.

You can apply this technique to perform an activity that hasn’t yet become a part of your life. What you need to do is study it in advance or have an initial guide that can help you navigate the path. For example, if you’re going to do resistance exercises, you could research what the proper techniques are, what training rhythms to follow, and the functions of different machines and weights. You can do these preliminary processes on your own or with the help of a professional guide. This way, it will be easier for you to practice task bracketing: visualizing the activity you’re going to do each day and knowing with some precision what steps are necessary to perform that activity, even before starting it and after completing it.

In my case, every time I go to the gym, I already know in advance which muscles I’m going to work on, how much time I’ll allocate to each muscle group, how I’ll do the post-workout stretching, whether I’ll use music or not, what clothing I should wear, and even what I can eat afterward, all to ultimately enjoy the satisfaction of having completed the task.

One of the factors that helped me establish the habit of writing was taking a course in creative writing. In this course, among many other things, I learned some prewriting techniques, which are processes that can and should be carried out before tackling a text. This tool can be used for any habit you want to develop.

This technique is wonderful because it can also serve as a fallback for extreme cases where you absolutely cannot perform the task. For example, if there’s a day when you physically can’t continue playing the guitar because your fingers hurt a lot or your back is bothering you, you can dedicate those 30 or 40 minutes a day to reviewing the theory around the chord you’re studying or a new way to play that harmonic progression, a new chord inversion, or watch a tutorial or video about it. This time will still count as time spent on the task, although clearly, the idea is to use this fallback only in extreme cases, let’s say once every 15 days or a month.

Task bracketing complete process. Image created with ByPeople Composer

Using External Elements with Caution

We talk about caution because the problem that arises when we use external elements to motivate ourselves, such as having good music, the company of a friend, or sunny weather, is that we must be extremely careful about how we dose these external factors. To maintain healthy dopamine levels, we must add these external factors almost randomly and in relatively small doses because we need to get accustomed to performing the task itself, not to these external factors. We need to get accustomed to practicing a new language, not to having the company of our friend or teacher while practicing this new language.

These external factors should be used randomly so that the brain doesn’t become accustomed to them, and we should use them in low and very deliberate doses. For example, when I go to the gym, I don’t always bring music; sometimes I simply don’t want that extra motivation because I don’t want to get used to having to listen to music since I can’t always count on it. Likewise, I don’t always go to the same gym; sometimes I exercise at home or in a park, and I do this deliberately to avoid getting accustomed to the gym environment. This approach to the habit has allowed me to carry out this task even while traveling or in conditions where I can’t go to the gym, meaning it has allowed me to make the habit truly reflexive, regardless of the circumstances.

The Satisfaction of Completing the Task Helps Form the Habit

When we carry out a challenging action but manage to complete it, even without motivation, knowing that it is a beneficial and healthy activity for us, our brain will feel the satisfaction of completing that task. This satisfaction will become inherent to the habit. In other words, dopamine will be generated for having completed the task, even if it’s a task we don’t enjoy that much. This small dopamine boost is what, over time and combined with the results, will really help motivate us and even make us start to like that task.

It’s important to understand that motivation should not come from the context or external factors, but rather we should seek motivation in the task itself, in the satisfaction of completing that task, even with difficulty. External factors can help us overcome the initial friction, but they should not be the reason for our satisfaction. By completing a task without having the motivation to do it, our brain associates that satisfaction or reward with the process of performing that task itself. Gradually, we’ll feel a bit more motivated because our brain has already linked that action to a benefit. It will become a bit easier each time because we’ll start to like feeling that dopamine in our body, and we’ll enjoy the extra motivation associated with that task more and more.

It’s Not 21 Days

Ever heard of the 21 day rule? We’ve heard that one too, and apparently this myth has very little to do with habits, per se. Its origins come from a 1960s self-help book titled “Psycho-Cybernetics” by american plastic surgeon and author Maxwell Maltz, in which he observes that it took his patients 21 days (give or take) to get used to their new appearance after cosmetic surgery.

There were no formal experiments or studies conducted to verify the claim, and additionally, the book applied this 21-day rule to many other aspects of life, such as setting a three week period as the time needed for people to get used to a new house or change their mind about their beliefs.

While certainly an interesting piece of trivia, the reality is a bit more complex. The 21 day myth became somewhat “common knowledge” over the years, and it wasn’t until over 40 years later, in 2009, that researchers conducted a study which yielded results that strongly countered the observations of Maltz.

In this study, it was found that it took anywhere from 18 to 254 days to develop new habits, with an average of around 66 days to reliably incorporate one of three activities into a daily routine. The biggest factor was consistent repetition.

Something else to keep in mind is that not all habits were created equal, and thus, the type of activity you’re working on developing as a habit is also a big factor. Teaching yourself a completely new skillset will naturally take much longer than simple activities like remembering to wash your hands or drink a glass of water in the morning.

For show and tell, a 2015 study found that new gym goers had to consistently attend at least four times every week, for a period of six weeks, in order to develop an exercise habit.

There’s another crucial aspect if we want to end up liking a task that we initially don’t enjoy, and that is, we must learn to be patient. If we’re overweight and have never exercised but want to lose 10 kilograms in a month, the change in diet and lifestyle can be too abrupt for us. It’s an overly ambitious and even unhealthy goal, one that is poorly formulated. Most people who start a diet and manage to lose weight often regain that lost weight over time, and the reason is that although they went through a weight loss process, that process wasn’t consolidated as a habit, as a change in the way of life. This is probably because the goal was so ambitious that it simply couldn’t be sustained over time.

This is why, if we want an activity to become enjoyable over time and turn into a habit, we must set realistic goals and be patient to begin seeing tangible results. There’s an idea that a habit is formed in 21 days, but this belief is false. In reality, it can take from 21 to even 250 days for a habit to truly consolidate. In other words, 21 days is the minimum time in which we could form a habit, but not the average time.

Moreover, 21 days, just three weeks, is too short a time to start seeing results for realistically set goals. For example, if we want to learn to play the guitar and have no prior musical knowledge, it will be very difficult for the guitar to sound correct and pleasant to the ear in just 21 days. So, if we’re anxious to see results in such a short time, we can become frustrated and give up the task. If we’ve set a long-term goal correctly, the time to achieve that goal should be between 6 months to a year. So, to begin seeing results, we should wait at least two or three months, and seeing results is an extra motivation that will help us continue with the habit. You can ask anyone who has learned to play an instrument, a new language, or run a marathon, and they’ll tell you the same: the first few months are very challenging. But by being patient and waiting for at least two or three months, results will start to appear, and that will motivate us to continue with the activity, possibly even with a particular fondness, as we’ll begin to associate that activity with a positive change in our lives. It will be another step toward making something we initially didn’t like turn into something we enjoy.

Learning About Compound Interest

In economics and investments, the concept of compound interest is very famous and valuable. Essentially, it suggests that even with a small return, given enough time, we can achieve great benefits. This same concept can and should be applied to the formation of new habits. Losing 10 kilograms in a month is physically possible, but it would require so much effort that without the necessary preparation, it can be detrimental to our health. Furthermore, it would require a significant daily time investment to achieve such a goal.

If we want to lose 10 kilograms and have neither a healthy diet nor the exercise habit, we should consider a goal of at least six months. This time frame is not only more prudent and realistic, but it allows us to set more achievable daily tasks. It’s much better to exercise for 20 or 30 minutes a day, every day, than to do a 4-hour exercise marathon only on weekends or to exercise for two hours daily with a strict diet but not continue beyond the first two months. Knowing how to pace yourself in terms of time and effort on a daily basis is crucial so that we can genuinely commit to performing the task every day (or almost every day) and truly consolidate it as a habit. In this way, we can achieve the desired objectives, even if it takes a little more time.

In conclusion, the most important factor in forming habits correctly is not waiting to be motivated to carry out the task but doing it even without the desire or the mood. Consistency over time will start to reward us with motivation, and we’ll begin to feel that we like that task and that we don’t feel as much friction in performing it. We can use external elements to help us overcome the initial friction, such as the company of a friend, having good music, or doing the activity in a group, etc. However, it’s crucial that these external factors are used with caution because what we’re aiming for is to get used to the activity itself, not the external factors. For an activity to truly become a habit, it should be independent of the context. Habits should be associated with medium or long-term goals, and these objectives should be set realistically to make a long-term commitment. The SMART technique can be used to define these objectives.

We must be patient and wait for at least two months to begin seeing results because the impatience that comes from wanting to see results very quickly can lead to frustration. Establishing a realistic daily time commitment for the habit is crucial. If we want results very quickly and set very long daily times, like two or three hours a day, it will be difficult to maintain that pace over time. So, it’s better to start with commitments of 20 minutes to an hour a day. It’s better to do something for 20 minutes every day than 4 hours only on weekends. Knowing and studying in advance the activity we want to carry out will help us implement the technique of task bracketing, which involves mentally visualizing the activity as a series of steps from before starting it until after completing it. Additionally, this knowledge will help us plan our daily activities better and break down our habit into smaller tasks that we can plan and visualize more easily. Cultivating habits is one of the most powerful methods we have not only to achieve our personal or professional goals but also to increase our overall life satisfaction and well-being.

Steps to build long-term habits. Image created with ByPeople Composer

Juan Pablo Sarmiento

System engineer from the National University of Colombia, with special interest over entrepreneurship, marketing, productivity and well-being.

Several projects and startups launched in over 20 years of experience.

Best Seller Deals

Check out time-limited deals on software and designs packs